|

|

|

|

The cover illustration of Masters of Surf Photography: Warren Bolster (click graphic to enlarge) |

His muscular body is crouched on a 7-foot 6-inch surfboard, and he seems to be exiting a tunnel of blue-white Pacific surf framing a distant mountain range on Tahiti's main island. Water drips off his back and the white spray that collects above the tube convinces the viewer to see-and even hear-the monster wave as it curls into the tube that challenges the best of surfers. Manoa Drollet is a surfer whose reputation has been built on managing the most dramatic of pipeline tubes in the South Pacific.

The photographer is even better known. He is Warren Edward Bolster whose pursuit of big and small waves have taken him and his camera to both coasts of the United States, specifically Virginia, Florida, and California as well as many Pacific Rim beaches, including Hainan Island off the coast of southwestern China. This prize photograph is on the front jacket of what promises to be one of several books illustrating his love of the ocean over some 30 years. And some of the book's photos include shots of the infamous Z-Boys on skateboards when Warren was editing SkateBoarder magazine in the late '70s. His has been a career with the same perilous up and down motion of the surfers and skateboarders he has captured on camera.

After six months of steadfast pursuit (including at least 50 e-mails and numerous phone calls), I caught up with Warren at a Waikiki hotel in company with his younger son Warren, Jr., age 9. They were on their way to Baby Queen's Surf just off Kalakaua Avenue. Waves used to be bigger there in Duke Kahanamoku's days in the early 1900s when Duke hung out with the other beach boys as he introduced the ancient sport of he'e nalu (sliding waves) to the rest of the world. In recent decades, the beach has become an outdoor classroom for aspiring young surfers who want to grow up to be like their heroes on the waves. Warren, Jr., is one of these. His hero is his dad, and he told me he wants to grow up to be just like him-a surf-photographer.

Deborah: In your book Master's of Surf Photography: Warren Bolster published by Surfer's Journal late last year, you explain: "I want people to see and feel what a surfer is seeing and feeling, to understand why it's so amazing to ride a wave. In a nutshell, that's why I take surf photos." So I'm one of those people. I swim but I don't surf. Make me understand the technique you used to create this board perspective that has earned you so much admiration from your peers in the profession. Where are you in this photo?

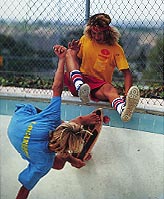

Jay Adams, Page 52 Masters of Surf Photography: Warren Bolster (click graphic to enlarge) |

Warren: I'm in a boat. And I'm using the remote control unit (a hand-held Futaba remote usually used in airplanes and cars.) As I look down the tube, I try to get as much of an angle as possible because the remote's radio waves are blocked quite a bit by ocean waves. In most of my surf photos, I'm actually a tiny spot in the distant scenery, but when I'm not, the surfer or tube blocks me out. At Teahupoo, where Manoa was surfing, the situation is ideal because I can be in a boat, relatively close to the camera, which is supported on the surfer's board by an aluminum mounting, looking straight down the throat of the tube, and capture the entire ride.

At places like Pipeline at Hawaii's north shore, I have to get as much of a tube angle (maybe a 45-degree angle to the tube) without getting too far away so I can see the surfer take off. This is more hit or miss since the tube can block the surfer from my view as well as block the radio waves. What I do is basically anticipate what's going to happen and start firing the remote before the surfer goes into the tube and hope that the water won't block the radio waves that allow the camera to function. I'm on the beach since in Hawaii I shoot a camera board from the beach or from jetties. A lot of the process is instinct and luck and guesswork. Surprisingly a lot of the sequences come out. In the case of Manoa, I shot almost an entire roll, 29 photos on that one wave within the time frame of 6 seconds (that's approximately 5 frames a second).

|

"There

was nowhere to go... So I stuck my head under water and hit my face

against the reef. I could feel the fin of this guy's board go by

on my neck and the back of my head."

|

Deborah: What kind of cameras do you use?

Warren: I've gone through various stages of cameras starting with the Pentax because a lot of my friends had them. In the 1970s I got a high-speed Cannon motor drive to shoot skateboarding when I was editor of SkateBoarder magazine. Then I used a Pentax II in my water housings. In the mid-80s I switched to Nikon during the auto-focus era of photography even though I was still shooting with manual cameras. I was spending so much time in helicopters that I couldn't afford the auto-focus cameras. Now I use Canon cameras exclusively. These are auto-focus with full service from Canon U.S.A., which is important for professional photographers isolated in Hawaii.

Deborah: Recently, you've received a lot of attention for your split-level images, a photo that peers above and below the water. One example in your book is captioned "Reef impact, Tavarua, 2000." What's going on here? You look like you're unconscious in the water. The photo shows your head above and your body in a surf shirt below the water.

Reef impact, Page 11 Masters of Surf Photography: Warren Bolster |

Warren: That was really a memorable experience for me-one of the many reef head injuries I've had. I was actually swimming with my camera during a rapidly dropping tide at Restaurants on Tavarua, Fiji, three years ago with surfing friends. I was swimming, and I was using a camera with over-under housing, which shoots in focus above and below in shallow water. The housing that protects the camera had a large Plexiglas dome. I was in shallow water and the tide was going out. The part of the reef where I was would be almost above water at low tide so I had to get out of there quickly. I'm walking around there because I wanted to see the reef below the water as well as see the surfers above water. And this really good surfer from Boston is hanging five or ten on a long board and he's heading right toward me. There was nowhere to go. I couldn't dive or anything. So I stuck my head under water and hit my face against the reef. I could feel the fin of this guy's board go by on my neck and the back of my head.

Deborah: So why do you look unconscious in the picture? What happened?

Warren: I swam out into deeper water to get out of further danger. I wasn't unconscious, but I was trying to keep my face from bleeding and I closed my eyes because I didn't want to look at the camera and indicate how shocked I was at what had just happened. I knew I had a lot of reef embedded in my face, and when Jon Roseman, one of the surfers, paddled over, he took more pictures and cleaned me up. Jon gets credit in the book for the photograph. I might have taken it myself. You can see my arms are out. I don't know which photos were which. I was helping him hold the camera halfway under because the camera housing is really buoyant

Manoa Drollet, Page 210 Masters of Surf Photography: Warren Bolster (click graphic to enlarge) |

Deborah: Why did you want a picture of yourself in such a dangerous situation?

Warren: To record my injuries. I consider these my war wounds, and I'm proud of them. It shows my dedication. Surfer ran a whole page of head wounds I had suffered in a 1977 issue. I've gotten skate boards right between the eyes, heavy wooden ones at full speed. I've had many damages from the water-housing boxes that slam into my face when I'm in the water setting up shots. There are all kinds of things that can happen, and I won't let anything deter me from getting my shot.

Deborah: Let's look backward in your life with a few questions? I read in your book that your mother gave you your first surfboard in 1963 when you were 16. Had you surfed before?

Warren: Yes, I had. When my parents and I passed through Hawaii on the way to my father's next assignment as First Secretary at the Tokyo embassy in 1957 and on our way back in 1959 to his next diplomatic assignment in Sydney, Australia, I tried the sport.

Deborah: Did you ever take lessons?

Warren: No, never. I remember the beach boys at the Hilton Hawaiian Village who rented me a surfboard. They didn't give me the sugar-cube-sized wax that they usually gave out. The boards are very slippery if they are not waxed. And I was just a kook. They must have gotten a kick out of watching this haole make a fool of himself. I didn't know anything back then.

Deborah: So how did you learn to surf?

Warren: I learned during my dad's tour in Australia. I just tried over and over and learned at the Sydney shore breaks. I watched and learned, watched and learned through trial and error. I was a long distance runner in high school. And as the Consul General's son, I got special treatment. I figured out how to sneak off the school bus, race to the beach, spend a few hours and get back to school for closing ceremonies on Fridays. And once I got into surfing, I quit everything else. There is nothing that compares with it.

Deborah: What about the other sports you've excelled in?

Warren: As I said, long distance running. I was a giant slalom skateboarder before there was safety gear, and that's how I broke my wrists and knees. I played baseball with Japanese kids in the late 50s when they still called it yakyu-not besabaru (derived from the English word baseball). I used to run in the men's league in Sydney. In one day I would run the 880, 440, the mile and the two-mile. I was running before the emphasis on marathons. I played basketball. I did all the sports because in my day there was no Nintendo, no TV.

Deborah: But surfing brought you the most satisfaction?

Warren: Absolutely. Surfing so far is more difficult than anything else I've tried. It's the pleasure of being in the ocean. Whether it's the American east coast or Australia. I was in California for 10 years. I visited Hawaii 30 times before I moved here in 1979, and I've lived here for 23 years. I've gone to Fiji 37 or 38 times. Tahiti, six times. I have increasingly chosen clear water and better conditions. Every angle and every turn I've taken in my profession has ended up being more interesting and creative, whether it's photography or surfing. Surfing never ceases to amaze me. As I've gotten older I've learned that the best surfers are the most relaxed with their arms below their waist most of the time. For example, Kenny G's song "Forever in Love" just puts me in a totally special place, especially in Fiji. I'm soo relaxed with all that's around me that, at my favorite spot in Fiji, "Swimming Pools," I can totally feel the beauty and surf better in an uncrowded environment.

Deborah: And then there's your work launching SkateBoarder magazine in the mid-1970s. There's a section in your book called "The Skateboarding Revival." Elsewhere in the book you're quoted as saying: "It wasn't just the new urethane wheels that caused the skate explosion-a lot of it was me."

Warren: That's pretty much bragging, but the ultimate look of the magazine, whether you like it or not, was my look, and it was all that I had to work with, and time has shown that with writer-photographer Craig Stecyk's influence-even if he contributed only one major article each issue when I was editing, that style continues today.

Deborah: How did you get the job as editor of SkateBoarder?

Warren: I was given the job because I was an enthusiastic skateboarder during my years in Virginia, and I had paid attention to the first popularity of skateboarding in the '60s. I was an associate editor and senior photographer for Surfer magazine, not to be confused with the current Surfer's Journal. I was also freelancing for Sports Illustrated and Rolling Stone, among others. So in 1975, my vivid descriptions of the new skateboard with urethane wheels persuaded Surfer's publishers to let me launch a new magazine. They gave me six months. I wrote almost all the articles, interviews, lots of "who's hot" columns, and I took 120 photos for the first issue. When SkateBoarder came out in 1975, it sold 100 percent. It was the first magazine on the sport, and later New Times magazine called it the leader in the sport and the best edited.

Deborah: How did the magazine do after the first issue?

Warren: It was published bi-monthly after its first issue-like other surf and skate magazines. Selling 40 percent is considered good in the magazine business and 100 percent is almost unheard of. SkateBoarder maintained a pretty constant sales rate of 72 percent. Then I became the first editor to take a surf or skate magazine monthly. I did the job by working day and night. In addition to me, there were maybe four other crucial staff members. And Craig Stecyk was freelancing for us. But I was getting strung out by work and travel and the publisher's demands of what I could and could not do. My last issue of SkateBoarder in 1979 had increased from 75 to 196 pages.

Deborah: And then?

Warren: The magazine was at its apex, but I was burned out. I quit Skateboarder, and the publishers hired two people to do my job. But they blew the momentum and the magazine went out of business in one-and-a-half years.

Deborah: When did you decide to come to Hawaii?

|

"

The Z-Boys were terrorizing the crowd before the event. And I was

standing up talking to Stecyk... and Jay or Tony or one of the Z-Boys

skated right between my legs."

|

Warren: In 1979. I was down and out and moved to Hawaii. The Kona coffee in Hawaii was stronger than anything. The bus system is the best in the world. It's warm all year. I had nowhere to go. I lost my house. My first wife. My car. Surfer and SkateBoarder came by and picked up my high-speed motor drive. I lost most of my camera equipment. I lost everything. And I'm an emotional person. It took me five years in Hawaii to get over my losses. If I had known about Southeast Asia, I would have come to the Pacific faster. I really dwelled on my losses. It was pity city, you know. It affected my second marriage, which broke down three years ago. From the highest paid photographer at Surfer, my annual income went to zero within one year. But like the country in recession, I recovered, and I have been working fairly steadily since.

Deborah: Getting back to the book. There's a riotous photograph of Jay Adams and Tony Alva in their teens. When was it taken?

Warren: I'm guessing the photo was taken in 1977. It was the first year after they became known as two of the Z-Boys. We're at San Diego State College. We snuck in. I won't go into details about everything that was going on. They're smoking a joint, you know, and showing off for the camera. I was on assignment for SkateBoarder as the senior photographer. I would often take photos, write the story and the photo captions. It was a great creative opportunity.

Deborah: In the wildly popular documentary Dogtown and the Z-Boys moderated by Sean Penn and released by Sony in 2001, you're-quoted as saying: "The world wasn't ready for the Z-Boys." What did you think of the movie?

Warren: Absolutely a great movie, primarily because of the editing. It captures the energy of Dogtown. But at that particular time the L.A. surfers were not really welcome up north or down south in California. They had a real genius documenting them, Craig Stecyk. He made all this happen. Stecyk's style is what the sport has copied up to this day. He made skateboarding what it is today. They can thank him.

|

Willy

Morris, Pinballs, 1986 Page 106, Masters of Surf Photography: Warren Bolster |

Tony

Alva and Jay Adams of Dogtown and Z-Boys fame

|

|

Deborah: So what's your opinion of Tony and Jay?

Warren: In my opinion, Tony Alva was the best all around skater, and he proved it. He came down to San Diego for the second world contest at Carlsbad Skate Park. There was downhill skating, slalom skating, all kinds of stuff. We had slalom for sure and free style and he won for overall skills. He was amazing, but he had a huge ego. So did Jay. Their egos are reflected in what they're doing today. And I would say it to their faces. They would argue with me.

Deborah: But you have to have an ego to do this crazy, scary stuff!

Warren: Of course! You need to have an ego to be alive. And you've got to hand it to them. They came from a rough part of town. Stecyk would come down to Surfer's in Dana Point, Orange County. where SkateBoarder's offices were located. And he would sit and talk about all the gangs in L.A. and all the different Mexican names, and this and that. I didn't know what the heck he was talking about. I didn't know about the Santa Monica pier. I knew for certain the Z boys weren't welcome anywhere. I think they took their attitude with them. And these guys were surfers originally!

Deborah: What were the Z-Boys really like in this peak period of the sport?

Warren: Well, Stecyk and I had a lot of freedom to play them up in the magazine. We found these underground guys who had a style very much like our surfing style at Sunset Cliffs in San Diego where I was living-an aggressive style of surfing. The Z-Boys could get into a tube in a very small space on the water and on cement. For example, in 1975, my right leg was in a brace, and I was attending the first contest at Delmar. The Z-Boys were terrorizing the crowd before the event. And I was standing up talking to Stecyk, and this is to show you what they were like. And Jay or Tony or one of the Z-Boys skated right between my legs. I freaked out. These guys are trying to skate between my legs. I had just had major surgery. They wanted to make themselves known to the world.

Deborah: Back to the subject you love best: surfing? What were you doing on China's Hainan Island?

Warren: We were invited by the Chinese Yachting Association to teach the Chinese team to surf. The surf was OK. But the trip ended up a bad thing. It was kind of scandalous. I'm a diplomat's son and the three other guys on the trip misbehaved. They put fireworks under my door in the hotel and burned the curtains and carpeting. And this was the nicest hotel in Hainan. We didn't find great surf. But we got an article out of it.

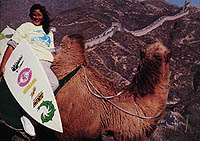

Deborah:

And you shot Rell Sunn, Makaha's surfing queen, holding her board on a

camel at China's Great Wall. Have you seen the recently released documentary

Heart of the Sea on Rell's surfing accomplishments as she battled

cancer until her death in 1998?

Deborah:

And you shot Rell Sunn, Makaha's surfing queen, holding her board on a

camel at China's Great Wall. Have you seen the recently released documentary

Heart of the Sea on Rell's surfing accomplishments as she battled

cancer until her death in 1998?

Warren: No, I haven't, but I consider Rell an official queen of Hawaii. She is the most special woman I have ever met. She opened a lot of doors back when a lot of surfers were gay. Sponsors were getting out because of this. Rell was the bastion of normality. She was respected by gays and everyone. She opened up Makaha on the west side of Oahu for surfing and photography.

Deborah: On another but related matter, I read in Surfing: A History of the Ancient Hawaiian Sport that in pre-missionary days Hawaiian men and women surfed together in the nude and even courted on the waves (which sounds like fun), and then American missionaries forbade surfing and other Polynesian pleasures in the early 19th century until King Kalakaua began reviving the sport at the end of the century. One of Rell's accomplishments was she established the first professional tour for women surfers in 1975. Why has it taken women so long to earn respect for their surfing skills?

Warren: There are many reasons they get less respect overall. It's very tough to look good and surf good for anybody, and the women have to deal with guys that want to get their share of waves. Probably aggression is one reason that women have become disgruntled with men and have joined ranks in disliking guys for the way they get "run over" in the mayhem. Also in the past, women could show up for a surf competition and with very little competition get a trophy. But that's changing because of Rell Sunn. She stood out in her day because she wasn't a lesbian. She could ride big waves and small and look good doing it. She was a great ambassador for the sport and lifestyle, and in her later years she was the best long boarder of all the women, and even better than some of the top men. Because of her, women now have their own place within the overall scheme of things, but there will always be some level of discrimination.

Deborah: The last photo in your book has been called by some the "million dollar wave."

Warren: It's not quite that. It was on the cover of the National Geographic calendar in the early '90s. The following year it was on the cover of Geo calendar. And it's been published all over the world. I shot the sun when it first hit the water at Oahu's Waimea around 7:30 and 8:30. The sun was between three hillsides, and as its rays hit the center of the beach, they spread out in both directions. I was down on the rocks on the church side of the road. I can't remember which lens I was using. Photos just happen. A lot of photography happens by magic. Waves are magic. In photography, the waves are timeless. Right from the start in 1972 I was successful in shooting empty waves. I'm still selling wave photos from 1972. Empty waves and little waves. It doesn't matter how big they are. People look at my photos and think, gosh, these waves look huge. But sometimes they're only six inches; they're ripples. They hardly break. And flat water. Just the beauty of the ocean!

Deborah: You've just returned from participating in a photo competition at the Telus World Snowboard and Skiing Festival at Whistler's Mountain near Vancouver. What's next?

Warren: I have been asked to take photos for an upcoming volume called A Week in the Life of America.

Deborah: Most of us remember-if we're a certain age- the 1986 publication of A Day in the Life of America as the best selling book on photography. Two hundred of the world's leading photojournalists were set loose on one day. The same producers of that volume-Rick Smolan and David Eliot Cohn-are teaming up for this project. I read at their Web site "www.america24-7.com" that that this will be the largest photo project in history, and "the watershed event of the new digital photograph age." During the week of May 12 to 18 hundreds of thousands of Americans will "create a national album." And you will be among them!

Warren: Yes. I was informed by a project editor that I was considered one of the top 20 photographers in the state. That makes 1,000 contract photographers who have been picked to participate. Of course Hawaii is competitive due to its beauty, so it's an honor that I don't necessarily believe, but with all the criticism and ups and downs in life, I'll just enjoy it for that, and the chance to show off surfing even more to the world.

Check out WarrenBolster.com

Buy

Masters of Surf Photography

Stick around braddah, and check out Deborah's interview with Achilles Gacis, Stuntman of Hawaii!

HOME

- LINKS - SEARCH

Columns - Features

- Interviews - Fiction

- GuestBook - Blogs

View ForbistheMighty.com for more

sin and wackiness!!!

Email Publisher